Academic Tone

I need help with…

Take the Learning Academic Writing Certificate

Take the Learning Academic Writing Certificate

Complete the Learning Academic English Certificate!

Precision & Clarity

Explanation and Examples

According to APA (2010), “Precision is essential in scientific writing; when you refer to a person or persons, choose words that are accurate, clear, and free from bias” (p. 71).

Clarity, in turn, means adhering to the following guidelines: “Devices that are often found in creative writing – for example: setting up ambiguity, inserting the unexpected, omitting the expected, and suddenly shifting the topic, tense, or person – can confuse or disturb readers of scientific prose” (APA, 2010, p. 65).

In short, your academic writing should be simple and to the point. It sounds easy, but this style of writing requires developing your writing skills and a dedication to the revision process.

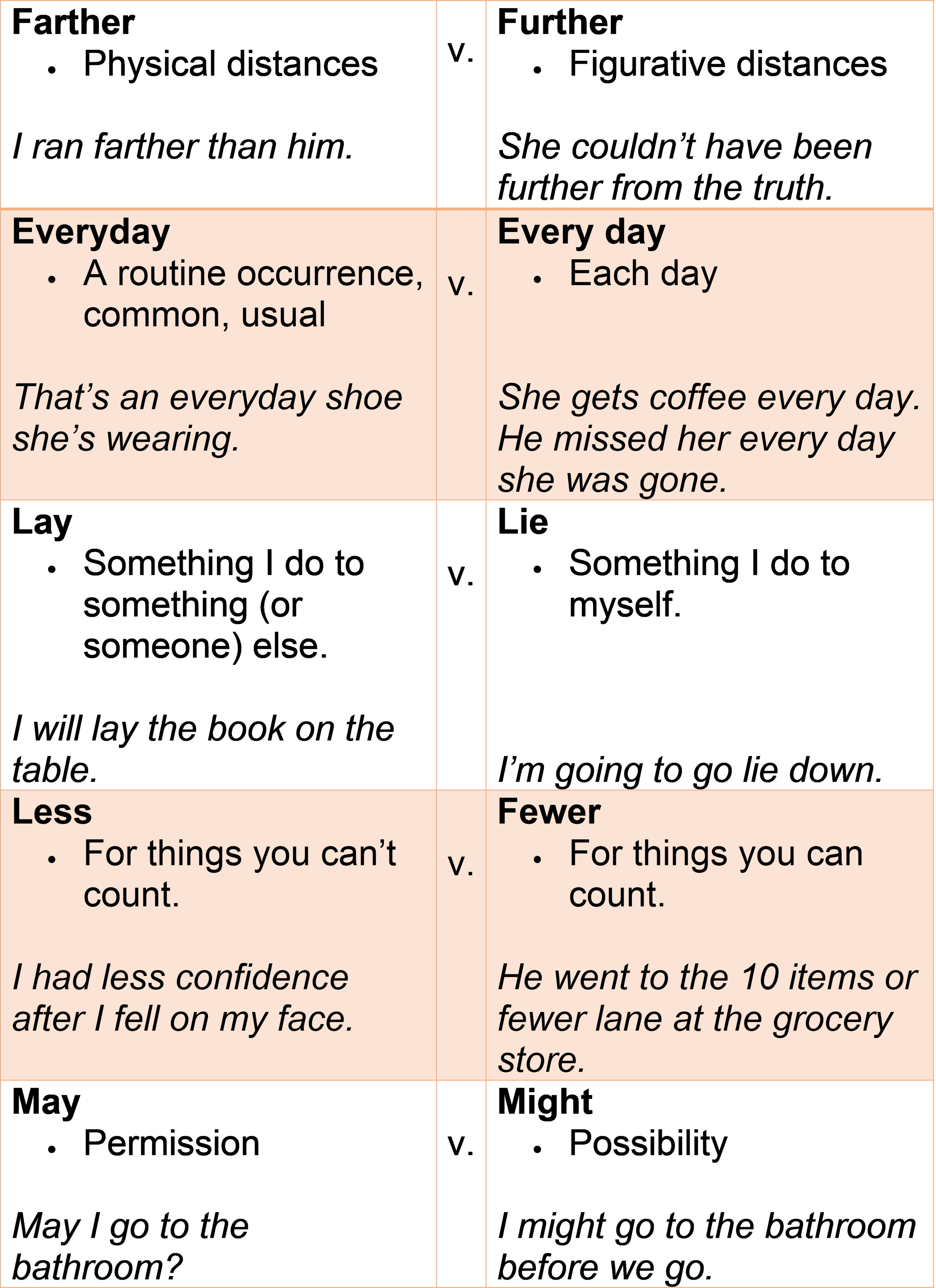

Tips for Precision

According to APA (2010), as a writer, you should “make certain that every word means exactly what you intend it to mean” (p. 68). Although not an exhaustive list of precise word choices, these are some of the most commonly misused words in academic writing:

Tips for Clarity

Use transitions

Pay attention to verb tense

Avoid clichés and colloquialisms

Avoid circumlocution

Avoid anthropomorphism

Avoid the editorial "we"

Use Transitions

“Readers will better understand you if you aim for continuity in words, concepts, and thematic development from the opening statement to the conclusion” (APA, 2010, p. 65).

This applies to each sentence, paragraph, section, and the overall paper. Here are some common, precise transitional words for academic writing:

Pay Attention to Verb Tense

Per APA, use the past tense to discuss things that occurred at a specific, definite time in the past:

The researchers included 15 subjects in their 2016 trial.

Marshall (2017) noted...

You might also use the present perfect tense when things did not occur at a specific, definite time or when things occurred in the past and are still happening, like this:

The researchers have been studying 15 subjects since 2016.

Researchers have found…

Verbs are active, vibrant, and full of meaning, and so you should let them do the "heavy lifting" in your writing. Use the active voice as much as possible, and avoid awkward verb phrases such as these:

Avoid Clichés and Colloquialisms

Language that cannot be universally translated might confuse some readers. In addition, common, everyday diction is not always appropriate in academic writing. Here are some common phrases to avoid:

The doors were closed to advancement

In light of recent research

The researchers were getting input from a focus group

My journey through my doctoral program

They have taken great strides in

Research has paved the way for

This has spun out of control

Can you think of other common cliches and colloquialisms to avoid in academic writing? Let us know your best example at onlinewritingcenter@thechicagoschool.edu.

Avoid Circumlocution

Circumlocution is a roundabout way of saying what you want to say; using several words to say something simple.

Instead of saying it like this:

“The participants in the study were six young people who have completed three years of elementary education and are not living in an urban area.”

Say it like this:

“The study will include six fourth grade students from a rural elementary school.”

Avoid Anthropomorphism

Anthropomorphism means assigning a human attribute to a nonhuman object, or using a verb that describes a human action with a nonhuman noun.

Incorrect:

Narrative research design studies the lives of individuals and obtains stories about their lives.

Correct:

Narrative design researchers study the lives of individuals and obtains stories about their lives.

Avoid Editorial “We”

According to APA (2010), “restrict your use of we to refer only to yourself and your coauthors…Broader uses of we leave your readers to determine to whom you are referring” (p. 69).

Unclear/Imprecise:

We know it is best for athletes to strength train, but not all coaches are trained in this. In our country, we all know the impact of homelessness on children.

Clearer and more precise (and more credible!):

Athletes need to strength train for ideal performance, but there is a lack of adequate coach training programs for sport-specific strength (Marshall, 2018). Homelessness is related to several negative outcomes for children and youth in the United States (Patters, 2017).

Economy of Expression

Explanation and Examples

Economy of expression means writers “Say only what needs to be said. The author who is frugal with words…writes a more readable manuscript….and increases the chances that the manuscript will be accepted for publication….Short words and short sentences are easier to comprehend than are long ones” (APA, 2010, p. 67).

Many novice research writers fall into familiar patterns of more informal, conversational style writing. Although this style is helpful in generating early drafts of your writing, your goal as a scholar practitioner (a.k.a., student) is to learn to write in a professional, objective manner.

It’s a myth that academic writing needs to sound “smart” or “complicated.” Readers need to understand exactly what you are saying, especially when you are conveying your methods of research, research questions, hypotheses, and so forth. There can be no margin for misinterpretation. Per APA (2010), to maintain economy of expression (in other words, to be concise) avoid the following:

Redundancy

Wordiness

Evasiveness (a.k.a, euphemism)

Overuse of the passive voice

Circumlocution (i.e., using more words than needed to say something simple)

Stating the obvious

Irrelevant observations or asides

Economy of expression also means eliminating any unnecessary phrasing from your writing. You can make sentences more concise by removing unnecessary phrasing, such as "I" statements and phrases that begin with "it" when "it" does not refer to something specific (e.g., a direct object). Similar expletive phrases include "there is" or "there are."

For example:

Active v. Passive Voice

Explanation and Examples

The active voice means that the subject of the sentence performs the action expressed in the verb. Or, more simply, the subject precedes the verb in the sentence, like this:

The student completed the final term paper a week before the due date.

The passive voice means the subject is no longer active, but instead is acted upon by the verb, like this:

The term paper was completed by the student a week before the due date.

Although not incorrect, overuse of the passive voice can cloud the meaning of your sentences and can make the sentence wordier than it needs to be. The active voice keeps sentences clearer and more concise. Consider these examples:

The consent form was completed.

Here, the passive voice leaves the reader wondering who completed the consent form. The active voice adds this clarity.

The client completed the consent form.

You can add clarity with the passive voice, like this:

The consent form was completed by the client.

However, using the active voice helps you make the sentence more concise, like this:

The client completed the consent form.

So, long story short, the APA manual places preference on the active voice because it allows you to harness verbs and write in a clear, direct, concise manner.

That said, the passive voice can be appropriate when you want to focus on the object or recipient of the action, not who initiated it. For example, use of the passive voice is common in a research paper’s methods section. Consider these examples:

The trials were conducted simultaneously.

Here, it makes sense that the focus is on the trials, not on who completed them (assuming this sentence appears in a Methods section, the audience assumes the initiator of the action is the researcher).

Another example, provided by APA, of when you might select the passive voice is when the recipient of the action is more important than the doer of the action. For example:

The President was shot.

In such a sentence, you want to place emphasis on the person shot, not the person who fired the shot.

Tone & Syntax

Using Syntax Effectively

Syntax refers to the rules that govern sentence structure in any given language; it is the way words are put together to form a sentence. The key to developing an academic tone, or what you might have heard referred to as a scholarly voice, is learning to vary your syntax while still adhering to the conventions of economy of expression and precision and clarity.

Consider this passage:

What’s working well here? For one thing, we know exactly what the subjects did, right? In this manner, the passage is exemplifying precision and clarity.

However… is it as concise as it could be? Would you consider this a scholarly voice or academic tone? Probably not.

Now, let’s look at a simple revision:

In this example, we have the same information still clear and precise, but presented with a much stronger academic tone.

The key to achieving this is writing with varied syntax.

Or, put another way, making sure that your sentences vary in length and structure so you maintain your reader’s interest without sacrificing the conventions of academic writing.

Quick Tip: Avoid several sentences in a row that are structured in the same way and are about the same length.

Here are some sentence structure variations you can incorporate into your own writing to enhance your academic tone:

Maintaining an Academic Tone by Avoiding Bias

According to APA (2010), researchers must be “committed both to science and to the fair treatment of individuals and groups, and this policy requires that authors. . .avoid perpetuating demeaning attitudes and biased assumptions about people in their writing” (pp. 70-71).

Tips for Reducing Bias - Gender (APA 3.12)

Gender is cultural and refers to role, not biological sex.

Sex is biological.

Do not use a masculine pronoun (e.g., he) to refer to both sexes.

Do not use masculine or feminine pronouns to define roles by sex (for example, always referring to nurses as she).

Transgender is an adjective used to refer to a person whose gender identity or expression is different from his or her sex at birth.

Do not use transgender as a noun.

For more information, see page pp. 73-75 in APA 6th edition.

Tips for Reducing Bias - Racial and Ethnic Identity (APA 3.14)

When using the word minority, use a modifier such as ethnic or racial to avoid association with meaning of being less than or oppressed.

Avoid describing groups differently. For example, Black Americans refers to color while Asian Americans refers to cultural heritage. Have parallel designations.

Do not use the term America to refer to the US population; be more specific

Racial and ethnic terms change often. Consult Guidelines for Unbiased Language at www.apastyle.org or 3.14 in the 6th edition of the APA manual for appropriate language and terminology.

Tips for Reducing Bias - Disabilities (APA 3.15)

Use language that maintains the integrity of all human beings. Avoid objectification and slurs.

In writing, use people-first language rather than focusing on disability. For example, say person with autism rather than an autistic or an autistic person.

Avoid offensive, condescending euphemisms when describing people with disabilities, such as special or physically challenged.

Tips for Reducing Bias - Age (APA 3.16)

The terms girl and boy should be used for individuals under 12 years of age.

The terms young man and young woman are appropriate for individuals aged 13 to 17 years of age.

The terms man and woman are used for anyone aged 18 years or more.

Do not use senior and elderly as nouns.

For more information on appropriate language concerning age, please see page 76 in APA 6th edition.