Plagiarism Prevention

Not sure where to get started? Click one of the menu options above or watch one of our helpful overview videos below!

What is Plagiarism and How Do I Know If I’ve Done It?

Overview of TCSPP Online Writing Center’s Plagiarism Prevention Guide

Why do I have to cite my sources

You very well may have the idea that plagiarism is a set in stone concept or that it is a valid construct based on facts and laws, but the reality is a little different.

Plagiarism is a cultural expectation. While copyright laws do exist, plagiarism in academia is based upon cultural values and expectations that have shaped the way in which students, faculty, and researchers are expected to use sources. Much like concepts of politeness, source usage actually differs greatly by culture. In this perspective, it is important to remember that different cultures’ approaches to source usage are not wrong or incorrect because they contrast with Western academic expectations of avoiding plagiarism.

The fact is simply that if you are enrolled in an academic program that is based on Western academic principles, you will culturally be expected to participate in avoiding plagiarism based on the cultural context in which you are taking courses. This is very similar to how you would practice different greetings or interaction norms based on your country of residence or where you visit. Just as you might give a hearty handshake with direct eye contact in Germany but a bow of differing length based on the person you are meeting in Japan, in Western academia, we will cite our sources.

So, what are the cultural expectations of Western academia?

To help understand Western academia’s cultural expectation of avoiding plagiarism, it is helpful to understand where this culture comes from. To do this, we will use Lewis’ (2010) three-pronged model of classifying cultures by their communication commonalities according to cultural behavior, cultural usage of information, and cultural trust. According to Lewis, all cultures have set rules and patterns of behaviors for these three categories, so they are very useful for comparing and contrasting cultures to better understand and respect them. We will use these three categories to understand plagiarism prevention as a cultural practice given that writing is a communication form, making Lewis’ framework a great fit for exploration.

Lewis suggests that there are three distinct types of cultures in communication: Linear-Active, Multi-Active, and Reactive cultures.

While you will not find academia in this list as a culture, start by finding your own to help contrast personal and academic perspectives on communication, writing, and plagiarism.

Figure 1. Richard Lewis’ (2010) classification of cultural communication types: linear-active, multi-active, and reactive. Adapted from Lewis (2020).

Linear-Active [Academia]

Linear-Active cultures, such as the United States, United Kingdom, and Germany, are driven by:

• emotionally disengaged and rationale communication

• task-oriented behavior

• decisive, factual planning

Multi-Active

Multi-Active cultures, such as those in Central Europe and Latin America, are driven by:

• loquacious communication

• warm and personal behavior

• impulsive planning

Reactive

Reactive cultures, such as those in Asia, are driven by:

• courteous and respectful communication

• compromise-oriented behavior

• amiable planning

These communicative characteristics shape the cultural behavior, information usage, style of trust, and writing style of the groups.

Behavioral Selection of Sources in Writing

Linear-Active [Academia]

Linear-Active cultures, such as the United States, United Kingdom, and Germany, prefer:

• facts, figures, data, and individual opinions

• linear writing organization

• a direct, logical approach rather than personal approaches

e.g., a native English writer prefers to use 'hard' data in writing—including academic research, statistics, and direct arguments

Multi-Active

Multi-Active cultures, such as those in Central Europe and Latin America, prefer:

• personal anecdotes, relationships between ideas

• flexible writing organization allowing interuptions

• a humanized, emotional approach instead of a detached approach

e.g., a Spanish writer may prefer to use personal sources in writing—including memories, personal anecdotes, and emotional reasoning

Reactive

Reactive cultures, such as those in Asia, prefer:

• respecting others' positions and group consensus

• circular writing structure organization

• prioritizing diplomatic and collectivist approaches over facts and opinions

e.g., a Chinese writer may avoid direct reference to sources and focus on the reader's opinions and feelings

Thus, academia requires linear organized writing that focusses on citing valid data and omitting personal opinions.

How Sources are Used in Writing

Linear-Active [Academia]

Linear-Active cultures, such as the United States, United Kingdom, and Germany, are data-oriented cultures:

• seeking information through research

• focussing on fine-points to prove an overall argument

• prefering information from collegues, reading, databases, and reports

e.g., a native English writer will conduct peer-reviewed research and discuss the fine points of an argument

Multi-Active

Multi-Active cultures, such as those in Central Europe and Latin America, are dialogue-oriented cultures:

• seeking information through conversation and contact with others

• focussing on the broader community implications

• prefering information from family, relatives, peers, reading, colleagues, and friends

e.g., a Hispanic writer may focus on the overall significance of the argument to the people involved, using personal stores

Reactive

Reactive cultures, such as those in Asia, are listening-oriented cultures:

• seeking information through official and familial sources

• focussing on listening to the other side

• prefering information from databases, relatives, media, social circles, and the counterargument

e.g., a Japanese writer may provide information fairly from all sides of the argument, using a mixture of personal and database sources

Thus, academia expects peer-reviewed data and an argument composed of supported points leading to a clear conclusion.

How Cultures Give and Earn Trust

Linear-Active [Academia]

Linear-Active cultures, such as the United States, United Kingdom, and Germany, are high-trust societies:

• Expects adherence to rules and respect for institutions of authority and their members

• Trusts consistency, scientific-based evidence, performance

• Sources must be cited to respect members of the institution and academic rules

Multi-Active

Multi-Active cultures, such as those in Central Europe and Latin America, are low-trust cultures:

• Expects flexibility in rules and respect for in-group relationships

• Trusts compassion, closeness, showing one's own weakness while not capitalizing on others' weaknesses

• Sources should be cited but with options for flexibility - they may be cited if relevant or indicating closeness with the source for the author's alignment

Reactive

Reactive cultures, such as those in Asia, are high and low trust cultures:

• Expects collective respect of the culture's values over personal desire

• Trusts protecting face, courtesy, personal sacrifice, reciprocity

• Sources do not need to be cited if they compromise someone's face or a cultural value (e.g., compromising the author's intelligence or the opposing party's comfort)

Thus, academia expects that trust will be earned through proving a written argument by providing sources and crediting all of the original authors.

Cultural Writing Style Expectations

Reviewing cultural behavior, information usage, and styles of trust, here are the expectations of each group in writing styles:

Linear-Active [Academia]

Linear-Active cultures, such as the United States, United Kingdom, and Germany, expect:

• linear paper organization, with a clear thesis to start, supporting subpoints, and a clear conclusion

• focus on analyzing an argument through details from sources

• direct, logical approach

• cites ALL sources

Multi-Active

Multi-Active cultures, such as those in Central Europe and Latin America, expect:

• personal organization, with room for flexible deviations from the main topic

• focus on the big picture overall

• emotional, humanized approach

• cites sources sometimes

Reactive

Reactive cultures, such as those in Asia, expect:

• circular organization, avoiding directly stating an argument

• focus on protecting the collective ideology

• indirect, face-protecting approach

• cites sources rarely

Academia as a Linear-Active Culture

Reviewing the contrast between linear-active, multi-active, and reactive cultures, here are the most important characteristics of academic culture to keep in mind when understanding plagiarism.

As a linear-active culture, academia expects unemotional writing that makes its point by following a logical deductively organized writing style.

Because academia is a data-oriented culture, it expects that all members will seek information through research and only use vetted sources.

Because academia is a high-trust society, expecting that all society members will follow societal rules and use scientific truth when making claims, citations are required on two fronts: validating what we say as true and providing credit to the scientific source honestly.

Reviewing these three characteristics explains why plagiarism is deemed an academic crime. Using sources without citation violates the behavioral expectations of the community, which asks all of its members to prove their arguments with research and to give credit to fellow members in honest communication.

In the Western academic world, plagiarism is considered an academic crime because it violates the behavior (linear-active), information usage (data-oriented), and trust (high-trust society) of the culture. Plagiarism is indirect in citing evidence-based sources, fails to reference the data used, and does not credit the institution or person who created the source, thereby, violating cultural standards.

What is plagiarism?

Aside from moral respect and obligations, there are also long-lasting consequences for plagiarism. Because plagiarism is so tied into cultural values, it is taken seriously and punished accordingly. For example, according to The Chicago School Academic Catalog and Student Handbook (2017), plagiarism is

intentionally or unintentionally representing words, ideas, or data from any source as one’s own original work. The use or reproduction of another’s work without appropriate attribution in the form of complete, accurate, and properly formatted citations constitutes plagiarism. Examples of plagiarism, include but are not limited to, copying the work of another verbatim without using quotation marks, revising the work of another by making only minor word changes without explanation, attribution, and citation, paraphrasing the work of another without the appropriate citation. A student is expected to produce original work in all papers, coursework, dissertation, and other academic projects (including case studies from internship or practicum sites) and to follow appropriate rules governing attribution that apply to the work product. Carelessness, or failure to properly follow appropriate rules governing source attribution (for example, those contained in the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association), can be construed to be plagiarism when multiple mistakes in formatting citations are made in the same paper. Further, a single example of failing to use quotation marks appropriately may be considered plagiarism.

PLAGIARISM AND ACADEMIC INTEGRITY AT TCSPP

Potential disciplinary outcomes for academic integrity violations at TCSPP include, but are not limited to, requirement of an Academic Development Plan, disciplinary action, and/or dismissal from TCSPP. Visit The Chicago School Academic Catalog and Student Handbook for full TCSPP policy on plagiarism and academic integrity.

Directly copying.

When another author’s ideas are directly copied into your writing without: (a) quotation marks around the quote; (b) an in-text citation; and (c) a page number. This claims the text as your own, breeching academic integrity. See more below.

Claiming something as fact.

When you do not provide a citation for: (a) information that is not commonly known; (b) statistics or data; or (c) an arguable claim that requires evidence. While not directly copying another’s words, the use of information that has been acquired from informational reading (online, Wikipedia, etc.) is still considered dishonest. See more below.

Failing to paraphrase.

A source can be incompletely paraphrased when: (a) you include ‘just a small number’ of words from the source without indicating which words are not yours; (b) you use the original sentence structure but insert synonyms; or (c) you do not provide a citation for source text that your paraphrased. See more below.

What does plagiarism look like?

Is this plagiarism?

Click on the boxes below:

When do I need a source?

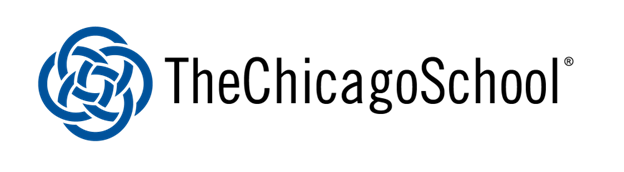

To avoid plagiarism, a few strategies can be used. The first thing to do is to decide if a source is needed. Following, if a source is used, the writer needs to decide how a source must be cited. In this process, a paraphrase strategy can be used. These are displayed below.

How do I present my source?

Do I need a source?

How do I use my sources?

This section covers the three steps to proper paraphrasing:

(1) Paraphrasing v. Direct Quoting

(2) How to Paraphrase at the Sentence-Level

(3) How to Paraphrase at the Paragraph-Level

(1) Paraphrasing v. Direct Quoting

Follow these basic guidelines to ensure that you are providing proper attribution to the ideas of others and, as such, avoiding plagiarism and academic integrity violations:

Direct Quoting

When you use the exact words of the cited material, you must:

put quotation marks around the word-for-word text (use a block quote for passages 40 words or longer)

use a signal phrase to introduce the quote – never begin a sentence with a quote

provide a specific page/paragraph number

Paraphrasing

When you use words, writing, facts, information, ideas, or data from any source besides your own mind, you must:

formally provide the source of that material in papers, presentations, or any other writing

use your own words and sentence structure

How do I paraphrase properly?

Never look at the source while you paraphrase; this often leads to using synonyms but keeping the original sentence structure/word order.

Use a 3:1 ratio: summarize three sentences of a source into one new sentence of your own words.

Try to draft your first paraphrase as if describing the source to a friend; this can sufficiently take the paraphrase away from the original wording and concerns for plagiarism.

Always incorporate your evaluation of the source in your paraphrase. This could include the significance of the source, a connection to another source, or how it proves your claims/argument.

Use one of the Online Writing and Learning Center’s paraphrase templates below.

(2) Paraphrasing at the Sentence Level

(3) Paraphrasing at the Paragraph Level

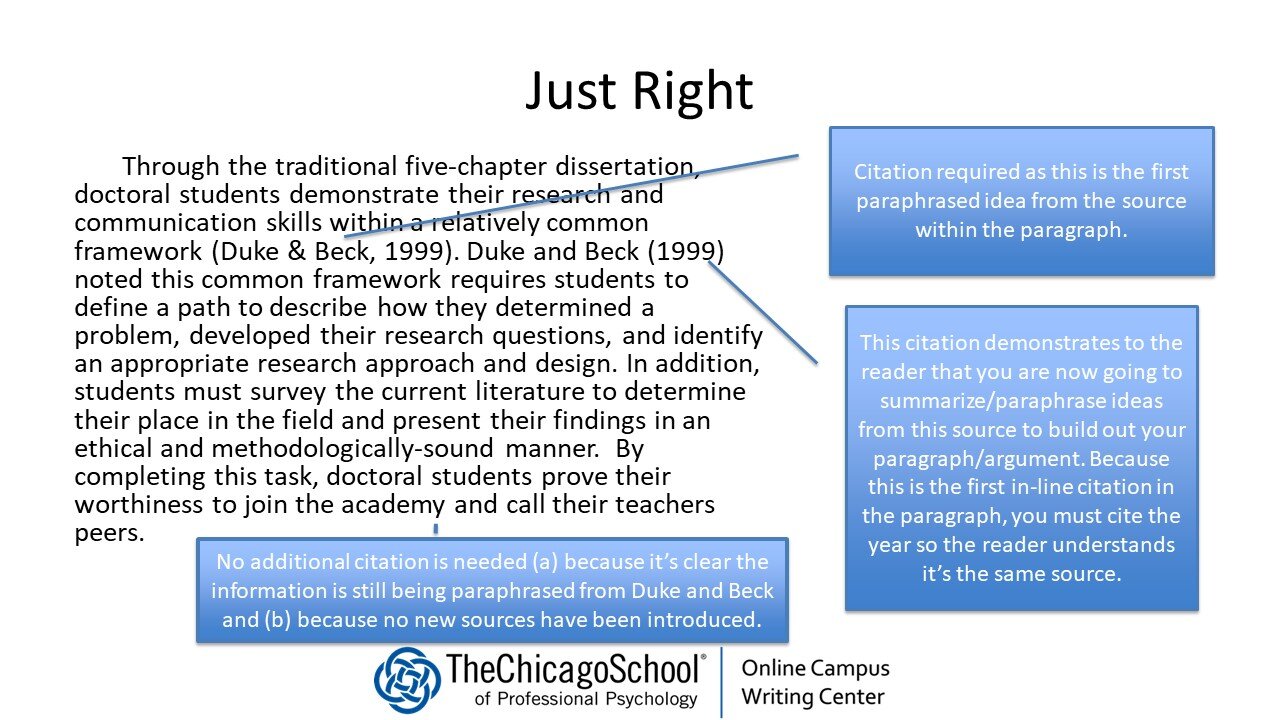

When we summarize a single source or even multiple sources, we can begin to feel like every sentence ends with the same parenthetical citation. This can really impact the readability of our work. To avoid this, you can follow this pattern of citation variation to create more flow and less redundancy in your citations.

More Than One Source

One Source

How do I know if I cited enough?

Under-Citation

Creates a concern for plagiarism by letting the reader think the paragraph was the author’s own work until the last sentence, which is cited as someone else’s idea.

Over-Citation

Creates distraction in reading because the same citation is present in each sentence, focusing on that rather than the material itself.

Just-Right

Credits the original author

Uses enough citations (parenthetical + in-line) to introduce the summary of the source

Uses signal phrases to indicate the summary is continuing, continuing to credit the original author and avoiding plagiarism

How do I know that it’s “just-right”?

Credits the original author

Uses enough citations (parenthetical + in-line) to introduce the summary of the source

Uses signal phrases to indicate the summary is continuing, continuing to credit the original author and avoiding plagiarism

How do I know if I plagiarize?

OWLC Plagiarism Assessment

When you feel confident in your understanding of TCSPP's and the APA's plagiarism regulations, repercussions, and recommended strategies, complete our Plagiarism Prevention Modules & Test.

Submit Your Paper to TurnItIn

You can submit any assignment to TII using our Academic Integrity Seminar TII assignment link. This assignment will NOT save your submission to the TII repository, and you are welcome to submit as many times as needed.

Dissertation and thesis students, if you are using this TII submission area to access a report for your Chair or current instructor, be sure you download your TII Report.